Nothing to see here – nothing has changed. That, at least, was the message the chancellor probably wants us to walk away with today, having consumed her first spring statement.

Consider the “current budget” – in other words the extent to which the government is having to borrow to finance day-to-day spending in the public sector.

This might seem like an arcane datapoint to focus on, but clearly someone in the Treasury is spending a lot of time thinking about it. Indeed, this was the very first statistic Chancellor Rachel Reeves mentioned in her speech today.

And for good reason. Last year Ms Reeves set herself a couple of fiscal rules, the most binding of which came back to the current budget. If she isn’t to fall foul of the rule, she needs to get the current budget into a surplus.

Last time around that surplus was £9.9bn – in other words she met the rule with £9.9bn “headroom”. Actually, to be even more geeky about it, the headroom was £9.93bn.

That raises a question: what was the headroom this time around? Lo and behold it was £9.93bn. Precisely the same number as the one last time around.

In other words, in statistical terms, the chancellor has blitzed the homework assignment she set herself. But now let’s look a little closer.

In fact, that latest £9.93bn figure is a product of some extraordinary fiscal contortions behind the scenes. Because a few weeks ago, when the Office for Budget Responsibility provided the Treasury with their forecasts of the state of the economy and the implications for the public finances, her headroom was not £9.93bn.

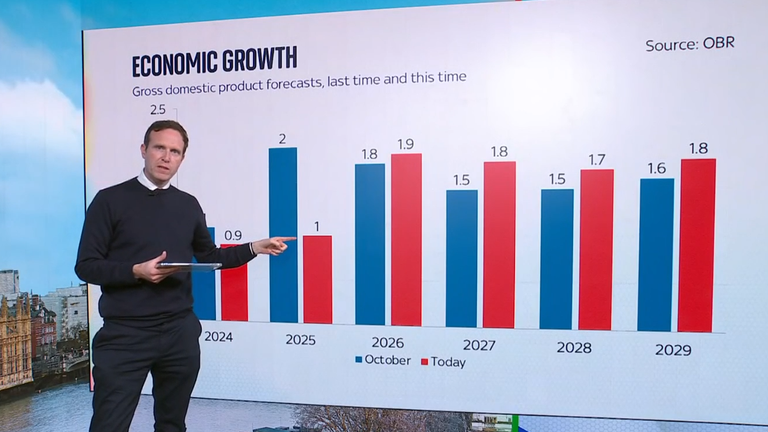

On the contrary, the entire headroom had been wiped out. Why? In large part because the economy is growing at a slower rate than previously expected and interest rates are higher. Put those two factors together and that adds up to more debt. It meant all of a sudden her £9.93bn surplus turned into a £4.1bn deficit.

Read more: Spring statement 2025 key takeaways

So how, you might ask, did the chancellor turn it back into the number she started with?

Answer, by deploying all sorts of fiscal levers. There are clampdowns on tax avoidance. There’s the redeployment of spending from aid to defence (since defence is mostly capital investment it has the benefit, from her perspective, of shoving a lot of spending into a different column in the governmental spreadsheet).

There’s a host of spending cuts (including reducing annual departmental spending in the years preceding the next election to the same rate Jeremy Hunt was targeting). And then there’s those welfare cuts you read about last week.

I could go on.

The welfare cuts from last week turn out to be far less effective at saving money than the government told everyone last week; the OBR also rapped the Treasury over the fingers for not being transparent enough with its figures. Those cuts will, according to the government’s own documents, push 350,000 or more people into poverty, including 50,000 children.

Beth Rigby analysis: Starmer has moved on to Tory territory

At this point (if you’re still reading), you’re probably asking yourself: why on earth is British economic policy being determined in large part with the objective of helping the chancellor to meet a fiscal rule she set herself and no one much cares about outside of Whitehall? And the truth is, there’s no particularly good answer to that question.

All the same: we end more or less where we began. The rule is met. The economy is weaker in the short run but slightly stronger in the longer run. But economic policy is not the same now as it was yesterday.